Was European Colonialism Racist?

The subjective legitimacy approach asks whether the people subject to colonialism treated it, through their beliefs and actions, as rightful. As Hechter showed, alien rule has often been legitimate in world history because it has provided better governance than the indigenous alternative.

Yet anti-colonial critics simply assert that colonialism was, in Hopkins’s words, “a foreign imposition lacking popular legitimacy.” Until very late, European colonialism appears to have been highly legitimate and for good reasons.

Millions of people moved closer to areas of more intensive colonial rule, sent their children to colonial schools and hospitals, went beyond the call of duty in positions in colonial governments, reported crimes to colonial police, migrated from non-colonized to colonized areas, fought for colonial armies, and participated in colonial political processes—all relatively voluntary acts.

Indeed, the rapid spread and persistence of Western colonialism with very little force relative to the populations and geographies concerned is prima facie evidence of its acceptance by subject populations compared to the feasible alternatives. The “preservers,” “facilitators,” and “collaborators” of colonialism, as Abernethy shows, far outnumbered the “resisters,” at least until very late: “Imperial expansion was frequently the result not just of European push but also of indigenous pull."

In Borneo, the Sultan of Brunei installed an English traveler James Brooke, as the rajah of his chaotic province of Sarawak in 1841. Order and prosperity expanded to such an extent that even once a British protectorate was established in 1888, the Sultan preferred to leave it under Brooke family control until 1946.

Sir Alan Burns, the governor of the Gold Coast during World War II, noted that “had the people of the Gold Coast wished to push us into the sea there was little to prevent them. But this was the time when the people came forward in their thousands, not with empty protestations of loyalty but with men to serve in the army... and with liberal gifts to war funds and war charities.

This was curious conduct for people tired of British rule.” In most colonial areas, subject peoples either faced grave security threats from rival groups or they saw the benefits of being governed by a modernized and liberal state. Patrice Lumumba, who became an anti-colonial agitator only very late, praised Belgian colonial rule in his autobiography of 1962 for “restoring our human dignity and turning us into free, happy, vigorous, and civilized men.” Chinua Achebe’s many pro-colonial statements, meanwhile, have been virtually airbrushed from memory by anti-colonial ideology. The few scholars who take note of such evidence typically dismiss it as a form of false consciousness.

The failure of anti-colonial critique to come to terms with the objective benefits and subjective legitimacy of colonialism points to a third and deeper failure: it was never intended to be “true” in the sense of being a scientific claim justified through shared standards of inquiry that was liable to falsification. The origins of anti-colonial thought were political and ideological. The purpose was not historical accuracy but contemporaneous advocacy. Today, activists associate “decolonization” (or “postcolonialism”) with all manner of radical social transformation, which unintentionally ties historic conclusions to present-day endeavors.

Unmoored from historical fact, postcolonialism became what Williams called a metropolitan flaneur culture of attitude and performance whose recent achievements include an inquiry into the glories of sadomasochism among Third World women and a burgeoning literature on the horrors of colonialism under countries that never had colonies.

Follow on Twitter: https://twitter.com/BasedCongo

Follow Professor Gilley on Twitter: https://twitter.com/BruceDGilley

Follow TRIGGERnometry on Twitter: https://twitter.com/triggerpod

#BruceGilley #Racism #colonialism

-

13:07

13:07

Belgian Congo

1 year agoIn Defence of British Colonialism

116 -

49:06

49:06

BrookeCerda

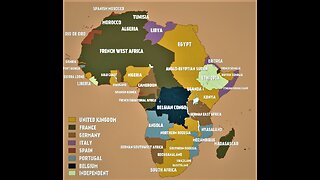

1 year agoEuropean Colonies before WW1 - White History Month

1.34K2 -

5:21

5:21

The History Speaks (Books Reader)

9 months agoMissions and Colonialism Christianity's Dual Role in Global Expansion

576 -

12:28

12:28

BrookeCerda

10 months agoThe Slave Masters Tryna Hide Whites on World Crimes

2993 -

11:39

11:39

TheDrNasirShaikhShow

5 months agoAFRICAN APOLOGY: Should KIng Charles Apologize For British Colonialism

58 -

27:40

27:40

Going Underground Episode Archive

1 year agoARCHIVE: The New Age of Empire-How Colonialism & Racism Still Rule The World (Prof. Kehinde Andrews)

75 -

21:31

21:31

New Discourses

5 months ago $0.18 earnedUnderstanding Settler Colonialism

1.78K4 -

25:25

25:25

RichardAzzouz

1 month agoThe Moroccan Rooted Slavery Mentality

60 -

10:38

10:38

NeutralityStudies

10 months agoColonialism Under A Different Name | The EU Abuses Africa Again | Clare Daly and Mick Wallace

38 -

56:33

56:33

ScheerPost

6 months agoSettler Colonialism, Thanksgiving and Gaza

1.92K