Beautiful Places In Iran Before Iran’s Islamic Revolution in 1979 Now The Be-Heading Start ?

This video reflects Iran during the time of the Shah when it was a modern, socially free, and a progressive nation with a blend of western and traditional values which made it a gem in Eurasia. These are a selection of photos from the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Background music is by Iranian singer Googoosh W0W. Before Iran’s Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iranian women were acquiring rights along with women in other parts of the world. Millions were in the workforce, including as government leaders, pilots, ambassadors and police officers. The Iranian Islamic Revolution wiped out those gains. Before the Islamic revolution of 1979, Iran was ruled by King Reza Shah Pahlavi (also known as the Shah). During his rule, he repressed dissent and restricted political freedoms but also pushed the country to adopt Western-oriented secular modernization, allowing some degree of cultural freedom and expanding Iran's economy and educational opportunities. Photos taken in the 1960s and 1970s reveal how much culture, fashion, and women’s freedom have changed in Iran during this period. Vintage photos capture everyday life in Iran before the Islamic Revolution, 1960s-1970s.

The Islamic Republic imposes strict rules on Iranian life. This extended photo collection shows Iranian society prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution and, it’s obvious that Iran was a very different world.

It was also a world that was looking brighter for women. And, as everyone knows, when things get better for women, things get better for everyone. After the revolution, the 70 years of advancements in Iranian women’s rights were rolled back virtually overnight.

The 1979 revolution, which brought together Iranians across many different social groups, has its roots in Iran’s long history. These groups, which included clergy, landowners, intellectuals, and merchants, had previously come together in the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–11. Efforts toward satisfactory reform were continually stifled, however, amid reemerging social tensions as well as foreign intervention from Russia, the United Kingdom, and, later, the United States.

The United Kingdom helped Reza Shah Pahlavi establish a monarchy in 1921. Along with Russia, the U.K. then pushed Reza Shah into exile in 1941, and his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi took the throne.

In 1953, amid a power struggle between Mohammed Reza Shah and Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the U.K. Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) orchestrated a coup against Mosaddegh’s government.

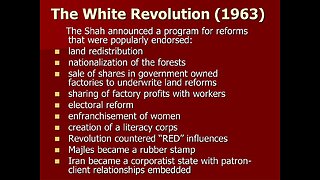

Years later, Mohammad Reza Shah dismissed the parliament and launched the White Revolution—an aggressive modernization program that upended the wealth and influence of landowners and clerics, disrupted rural economies, led to rapid urbanization and Westernization, and prompted concerns over democracy and human rights. The program was economically successful, but the benefits were not distributed evenly, though the transformative effects on social norms and institutions were widely felt.

Opposition to the shah’s policies was accentuated in the 1970s, when world monetary instability and fluctuations in Western oil consumption seriously threatened the country’s economy, still directed in large part toward high-cost projects and programs. A decade of extraordinary economic growth, heavy government spending, and a boom in oil prices led to high rates of inflation and the stagnation of Iranians’ buying power and standard of living. In addition to mounting economic difficulties, sociopolitical repression by the shah’s regime increased in the 1970s. Outlets for political participation were minimal, and opposition parties such as the National Front (a loose coalition of nationalists, clerics, and non-communist left-wing parties) and the pro-Soviet Tūdeh (“Masses”) Party were marginalized or outlawed.

The social and political protest was often met with censorship, surveillance, or harassment, and illegal detention and torture were common.

For the first time in more than half a century, the secular intellectuals—many of whom were fascinated by the populist appeal of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a former professor of philosophy in Qom who had been exiled in 1964 after speaking out harshly against the shah’s recent reform program—abandoned their aim of reducing the authority and power of the Shiʿi ulama (religious scholars) and argued that, with the help of the ulama, the shah could be overthrown.

In this environment, members of the National Front, the Tūdeh Party, and their various splinter groups now joined the ulama in broad opposition to the shah’s regime.

Khomeini continued to preach in exile about the evils of the Pahlavi regime, accusing the shah of irreligion and subservience to foreign powers.

Thousands of tapes and print copies of Khomeini’s speeches were smuggled back into Iran during the 1970s as an increasing number of unemployed and working-poor Iranians—mostly new migrants from the countryside, who were disenchanted by the cultural vacuum of modern urban Iran—turned to the ulama for guidance.

The shah’s dependence on the United States, his close ties with Israel—then engaged in extended hostilities with the overwhelmingly Muslim Arab states—and his regime’s ill-considered economic policies served to fuel the potency of dissident rhetoric with the masses. Outwardly, with a swiftly expanding economy and a rapidly modernizing infrastructure, everything was going well in Iran.

But in little more than a generation, Iran had changed from a traditional, conservative, and rural society to one that was industrial, modern, and urban.

The sense that in both agriculture and industry too much had been attempted too soon and that the government, either through corruption or incompetence, had failed to deliver all that was promised was manifested in demonstrations against the regime in 1978.

Amidst massive tensions between Khomeini and the Shah, demonstrations began in October 1977, developing into a campaign of civil resistance that included both secular and religious elements.

The protests rapidly intensified in 1978 as a result of the burning of Rex Cinema which was seen as the trigger of the revolution, and between August and December of that year, strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country.

On 16 January 1979, the Shah left Iran and went into exile as the last Persian monarch, leaving his duties to a regency council and Shapour Bakhtiar, who was an opposition-based prime minister.

Ayatollah Khomeini was invited back to Iran by the government, and returned to Tehran to a greeting by several thousand Iranians.

The royal reign collapsed shortly after, on 11 February, when guerrillas and rebel troops overwhelmed troops loyal to the Shah in armed street fighting, bringing Khomeini to official power.

Iranian people voted in a national referendum to become an Islamic republic on 1 April 1979 and to formulate and approve a new theocratic-republican constitution whereby Khomeini became the supreme leader of the country in December 1979. The revolution was unusual for the surprise it created throughout the world. It lacked many of the customary causes of revolution (defeat in war, a financial crisis, peasant rebellion, or disgruntled military).

Moreover, it occurred in a nation that was experiencing relative prosperity; produced profound change at great speed; was massively popular; resulted in the exile of many Iranians.

The Revolution replaced a pro-Western secular authoritarian monarchy with an anti-Western Islamist theocracy based on the concept of velayat-e faqih (or Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists) straddling between authoritarianism and totalitarianism. Declaring himself Allah’s own messenger, Ayatollah Khomeini’s vision for Iran was a return to conservative Islamic values and a purge of Western influences.

This involved a radical reinterpretation of Islamic social guidelines and a regression to religious standards practiced over a thousand years ago. The modest rights women had achieved under the Shaw were summarily revoked by Khomeini.

Professional women were fired in masse and encouraged to take up household duties, caring for children and husbands. Quickly, every aspect of female life was brought under strict government control.

New laws were passed banning Western clothing and requiring that women remain completely covered by a traditional Islamic hijab in public at all times. No hair could be visible; no open-toed shoes.

A special government agency was created to enforce the moral dress code; the Prevention of Vice and Enjoining of Virtue center dealt exclusively with women found to be in violation of the dress code in any way. The military training of the revolutionary guards was expanded to include spotting imperfections in the dress code and policing women.

In December 2018, muslim jihadis brutally killed 28-year-old Maren Ueland of Norway and 24-year-old Louisa Jespersen of Denmark after sexually assaulting & raping them. The women were beheaded. One of the beheadings was filmed and posted on social media by the muslim killers. Sex Slavery New Face of Oppression of Women in Iran Twenty-five years after the overthrow of the Shah, sex trafficking is flourishing in Iran under a tyrannical system of gender apartheid. The authors believe that only the end of the fundamentalist Islamic regime will free women and girls.

Twenty-five years ago, the Shah of Iran was overthrown by a diverse set of groups, some of which supported a secular and democratic government. The pro-democracy groups were outmaneuvered and then violently attacked by the Islamic fundamentalists, who went on to seize control of the country.

A measure of Islamic fundamentalists’ success in controlling this society is the depth and totality with which they suppress the freedomand rights of women. Over the past 25 years, the Islamic fundamentalists in Iran have expended tremendous amounts of time and effort controlling, harassing, and punishing women and girls in the name of Islam. They have passed and enforced humiliating and sadistic rules and punishments on women and girls, enslaving them in a system of segregation, forced veiling, second-class status, lashing and stoning to death.

Donna M. Hughes

The repressive gender apartheid in Iran is generally well known. Less well known is that Iran has joined the growing global criminal activity of sex trafficking. Exact numbers of victims are impossible to obtain, but according to an official source in Tehran, there has been a seven-fold increase in the number of teen-age girls in prostitution. The magnitude of this statistic conveys how rapidly this form of abuse has grown. In Tehran, there are an estimated 84,000 women and girls in prostitution, many of them are on the streets, others are in the 250 brothels that reportedly operate in the city. The trade is also international. Thousands of Iranian women and girls have been sold into sexual slavery abroad.

Sex-Slave Trade Highly Profitable

The head of Iran’s Interpol bureau believes that the sex slave trade is one of the most profitable activities in Iran today, and government officials themselves are involved in buying, selling and sexually abusing women and girls.

Many of the girls come from impoverished rural areas. Drug addiction is epidemic throughout Iran, and some addicted parents sell their children to support their habits. High unemployment–28 percent for youth between 15 and 29 years of age and 43 percent for women between 15 and 20–is a serious factor in driving restless youth to accept risky offers for work.

Popular destinations for victims of the sex slave trade are the Arab countries in the Persian Gulf. According to the head of the Tehran province judiciary, traffickers target girls between 13 and 17 to send to Arab countries. The number of Iranian women and girls who are deported from Persian Gulf countries indicates the magnitude of the trade. Upon their return to Iran, the Islamic fundamentalists blame the victims and often physically punish and imprison them. The women are examined to determine if they have engaged in "immoral activity." Based on the findings, officials can ban them from leaving the country again.

Police have uncovered a number of prostitution and slavery rings operating from Tehran that have sold girls to France and Britain. In the northeastern Iranian province of Khorasan, local police report that girls are being sold to Pakistani men as sex-slaves. The Pakistani men marry the girls, ranging in age from 12 to 20, and then sell them to brothels in Pakistan.

Street Children and Runaways

One factor contributing to the increase in prostitution and the sex slave trade is the number of female teens who are running away from home. Sources inside Iran say the girls are rebelling against fundamentalist imposed restrictions on their freedom, domestic abuse and parental drug addictions. Unfortunately, in their flight to freedom, the female teens find more abuse and exploitation. As a result of runaways, in Tehran alone there are an estimated 25,000 street children, most of them girls. Pimps prey upon street children, runaways and vulnerable high school girls in city parks. Indications are that 90 percent of female runaways will end up in prostitution.

The exposure of sex slave networks in Iran by some arrests that have been made provide indications that many mullahs and officials are involved in the sexual exploitation and trade of women and girls. Women who are arrested for prostitution say they must have sex with the arresting officer. There are reports of police locating young women for sex for the wealthy and powerful mullahs.

In cities, shelters have been set up to provide assistance for runaways. Some allege that the officials who run these shelters are often corrupt; they run prostitution rings using the girls from the shelter.

Sex Trade and Theocracy

Some may think a thriving sex trade in a theocracy with clerics possibly acting as pimps is a contradiction in a country founded and ruled by Islamic fundamentalists. In fact, this is not a contradiction.

First, exploitation and repression of women are closely associated. Both exist where women, individually or collectively, are denied freedom and rights. Second, the Islamic fundamentalists in Iran are not simply conservative Muslims. Islamic fundamentalism is a political movement with an ideology that considers women inherently inferior in intellectual and moral capacity. Fundamentalists hate women’s minds and bodies.

When he took power, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini set up a theocracy based on the principle of "velayat-e-faqih," or rule by the supreme religious leader under which he and now his successor Ayatollah Ali Khamenei have final say over all decisions in Iran.

In such a religious dictatorship, one cannot appeal to the rule of law for justice for women and girls. Women and girls have no guarantees of freedom and rights and no expectation of respect or dignity from the Islamic fundamentalists.

We believe that only the end of the fundamentalist regime will free women and girls from all the forms of slavery they suffer. There is a growing movement in Iran to oust the ruling clergy. Pro-democracy activists are proposing that an internationally monitored election–a referendum–be held on the form of government that will rule Iran. There is hope that this will be the first step to establish a secular and democratic Iran. Women across Iran are risking their safety–and often their lives–to demonstrate against the Iranian regime and call for the referendum. Democracy in Iran is their only hope for the future.

The Iranian authorities have embarked on an execution spree, killing at least 251 people between 1 January and 30 June 2022, according to research by the Abdorrahman Boroumand Centre for Human Rights in Iran and Amnesty International. The organizations warned that if executions continue at this horrifying pace, they will soon surpass the total of 314 executions recorded for the whole of 2021.

Most (146) of those executed in 2022 had been convicted of murder, amid well-documented patterns of executions being systematically carried out following grossly unfair trials. At least 86 others were executed for drug-related offences which, according to international law, should not incur the death penalty. On 23 July, the authorities executed one man in public in Fars province, after a halt in public executions for two years during the pandemic.

“During the first six months of 2022, the Iranian authorities executed at least one person a day on average. The state machinery is carrying out killings on a mass scale across the country in an abhorrent assault on the right to life. Iran’s staggering execution toll for the first half of this year has chilling echoes of 2015 when there was another shocking spike,” said Diana Eltahawy, Deputy Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa at Amnesty International.

“The renewed surge in executions, including in public, shows yet again just how out of step Iran is with the rest of the world, with 144 countries having rejected the death penalty in law or practice. The Iranian authorities must immediately establish an official moratorium on executions with a view to abolishing the death penalty completely,” said Roya Boroumand, Executive Director of Abdorrahman Boroumand Centre, an Iranian human rights organization.

The figures compiled by Abdorrahman Boroumand Centre and Amnesty International draw from a variety of sources, including prisoners, relatives of those executed, human rights defenders, journalists, and reports by state media as well as independent media outlets and human rights organizations.

The real number is likely higher, given the secrecy around the number of death sentences the authorities impose and carry out.

Mass executions in prisons

Information gathered shows that since early 2022, the authorities have regularly carried out mass executions across Iran.

On 15 June 2022, authorities in Raja’i Shahr prison in Alborz province executed at least 12 people. This followed the mass execution of at least 12 people on 6 June 2022 in Zahedan prison in Sistan and Baluchistan province.

On 14 May 2022, the authorities executed nine people: three in Zahedan prison, one in Vakilabad prison in Khorasan-e Razavi province, four in Adelabad prison in Fars province, and one in Dastgerd prison in Esfahan province. According to an informed source interviewed by Amnesty International in June 2022, since early 2022, authorities in Raja’i Shahr prison, which has one of the largest numbers of people on death row, have been executing five people each week on average, with up to 10 executions carried out some weeks. The figure corresponds with public letters written separately in recent months by human rights defenders Saeed Eghabli and Farhad Meysami who are unjustly jailed in Raja’i Shahr prison. The former referred to weekly executions of up to 10 people in Raja’i Shahr prison while the latter warned that the total number of executions there could surpass 200 by the end of 2022.

The informed source also said that Raja’i Shahr’s associate prosecutor (dadyar) recently told prisoners that the Office for the Implementation of Sentences had written to the families of about 530 murder victims, asking them to decide whether to pardon or seek the execution of those convicted of murdering their kin by late March 2023.

The same source said repeated statements by the head of judiciary Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei and other senior judicial officials in recent months about the need to address prison overcrowding have raised widespread fears among prisoners that the rise in executions is related to official efforts to reduce prisoner numbers. The fears expressed are supported by past patterns monitored by Abdorrahman Boroumand Centre that indicate spikes in executions coincide with periods when the authorities make repeated public statements about their goals to address case backlogs and reduce overcrowding.

Renewed surge in drug-related executions

The execution of at least 86 people for drug-related offences in the first six months of 2022 has grim echoes of the authorities’ anti-narcotics practices in the years between 2010 and 2017, when most recorded executions were for drug-related offences.

In November 2017, following intense international pressure, which included several European countries cutting off funds to anti-narcotics operations by Iran’s law enforcement forces, the authorities adopted some legal reforms to eliminate the death penalty for certain drug-related offences.

Between 2018 and 2020, the authorities considerably reduced drug-related executions. However, in 2021, at least 132 people were executed for drug-related offences, accounting for 42% of overall recorded executions and representing more than a five-fold rise from 2020 (23).

The international community, including the EU and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, must urgently undertake high-level interventions, calling on the Iranian authorities to end the death penalty for all drug-related offences. They must ensure that any cooperation in anti-drug trafficking initiatives does not directly or indirectly contribute to the arbitrary deprivation of the right to life, which is the defining characteristic of Iran’s anti-narcotics operations.

At least 65 (26 %) of those executed since 2022 were members of Iran’s impoverished Baluchi ethnic minority, who make up about 5% of Iran’s population. Over half (38) were executed for drug-related offences.

“The disproportionate use of the death penalty against Iran’s Baluchi minority epitomizes the entrenched discrimination and repression they have faced for decades and further highlights the inherent cruelty of the death penalty, which targets the most vulnerable populations in Iran and worldwide,” said Roya Boroumand.

Abdorrahman Boroumand Centre and Amnesty International oppose the death penalty without exception regardless of the nature of the crime, the characteristics of the offender, or the method used by the state to kill the prisoner. The death penalty is a violation of the right to life and the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment.

Background The number of executions in Iran in 2021 was the highest since 2017. The rise began in September 2021, after the head of judiciary, Ebrahim Raisi, rose to the presidency and the Supreme Leader appointed a former Minister of Intelligence, Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei, as the new head of judiciary.

The Iranian authorities carried out one public execution in 2022, none in 2021, one in 2020, 13 in 2019 and 13 in 2018. Official announcements indicate that in early 2022, at least two other people in Esfahan province and one person in Lorestan province were sentenced to be executed in public.

The death penalty is imposed in Iran following trials that are systematically unfair, with torture-tainted “confessions” routinely used as evidence. The UN Special Rapporteur on Iran has stated that “entrenched flaws in law … mean that most, if not all, executions are an arbitrary deprivation of life.”

Under Iranian law, the death penalty applies to numerous offences including financial crimes, rape and armed robbery. Activities protected by international human rights law such as consensual same-sex sexual conduct, extramarital sexual relations and speech deemed “insulting to the Prophet of Islam” as well as vaguely-worded offences such as “enmity against God” and “spreading corruption on earth” are also punishable by death.

Beheading was a standard method of execution in pre-modern Islamic law. By the end of the 20th century, its use had been abandoned in most countries. Beheading is still a legal method of execution in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Yemen. In Iran, beheading was last used in 2001, according to Amnesty International; however, it is no longer in use. In recent times, extremist Jihadist organizations such as ISIS and Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad have used beheading as a method of killing captives. Since 2002, ISIS have circulated beheading videos as a form of terror and propaganda. Their actions have been condemned by militant and other terrorist groups, as well as by mainstream Islamic scholars and organizations. The use of beheading for punishment continued well into the 20th century in both Islamic and non-Islamic nations. When done properly, it was once considered a humane and honorable method of execution. There is a debate as to whether the Quran discusses beheading. Two surahs could potentially be used to provide a justification for beheading in the context of war:

When the Lord inspired the angels (saying) I am with you. So make those who believe stand firm. I will throw fear into the hearts of those who disbelieve. Then smite the necks and smite of them each finger. (8:12)

Now when ye meet in battle those who disbelieve, then it is smiting of the necks until, when ye have routed them, making fast of bonds; and afterward either grace or ransom 'til the war lay down its burdens. (47:4)

Among classical commentators, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi interprets the last sentence of 8:12 to mean striking at the enemies in any way possible, from their head to the tips of their extremities. Al-Qurtubi reads the reference to striking at the necks as conveying the gravity and severity of the fighting. For al-Qurtubi, al-Tabari, and Ibn Kathir, the expression indicates the brevity of the act, as it is confined to battle and is not a continuous command.

Some commentators have suggested that terrorists use alternative interpretations of these surahs to justify beheading captives, however there is agreement among scholars that they have a different meaning. Furthermore, according to Rachel Saloom, surah 47:4 goes on to recommend generosity or ransom when waging war, and it refers to a period when Muslims were persecuted and had to fight for their survival. Beheading was the normal method of executing the death penalty under classical Islamic law. It was also, together with hanging, one of the ordinary methods of execution in the Ottoman Empire.

Currently, Saudi Arabia is the only country in the world which uses decapitation within its Islamic legal system. The majority of executions carried out by the Wahhabi government of Saudi Arabia are public beheadings, which usually cause mass gatherings but are not allowed to be photographed or filmed.

Modern instances of Islamist beheading date at least to the early 1990s.

At the beginning of the Bosnian War (1992-95), anywhere from 500-6,000 foreign volunteers (mostly from the Gulf States, the Levant, and South Asia) travelled to Bosnia (with the support of the Croatian government at the time) to volunteer for jihad and fight alongside the Bosniaks that were being heavily persecuted against. Most came into Bosnia and Herzegovina under the guise of being volunteer aid workers and freelance journalists, complete with fake identification cards and passports. When they arrived in Bosnia, they formed a volunteer brigade called the El-Mudžahid along with some local Bosniak volunteers, and were affiliated with the 3rd Corps (although they weren't officially absorbed into the Bosnian Army, and also had quite a bit of internal conflict and strife amongst the two organizations due to differing views on Islam, culture, and politics). The El-Mudžahid were notorious for their brutal tactics and ferocious fighting on the battlefield, along with how they treated their POW's. There was several cases of decapitation that happened to POW's, along with being tortured severely before-hand. In the most famous case, there is an amateur video (along with a photo) taken of a foreign fighter decapitating and holding the severed head of a Serb POW up to the camera. Before the subsequent video was taken, 2 Serb POW's (Momir Mitrović and Predrag Knežević) were captured, subjected to severe beatings and had their hands and feet bound together for hours on end. After beating and torturing the prisoners for hours, the foreign fighter slit the throats of the two Serb POW's and then proceeded to decapitate them, to which after they held the head of one of the POW's up in "celebration". There also have been many other documented cases of decapitation happening at the hands of El-Mudžahid during the Bosnian War. Islamic Fundamentalism and the Sex Slave Trade in Iran A measure of Islamic fundamentalists’ success in controlling society is the depth and totality with which they suppress the freedom and rights of women. In Iran for 25 years, the ruling mullahs have enforced humiliating and sadistic rules and punishments on women and girls, enslaving them in a gender apartheid system of segregation, forced veiling, second-class status, lashing, and stoning to death.

Joining a global trend, the fundamentalists have added another way to dehumanize women and girls: buying and selling them for prostitution. Exact numbers of victims are impossible to obtain, but according to an official source in Tehran, there has been a 635 percent increase in the number of teenage girls in prostitution. The magnitude of this statistic conveys how rapidly this form of abuse has grown. In Tehran, there are an estimated 84,000 women and girls in prostitution, many of them are on the streets, others are in the 250 brothels that reportedly operate in the city. The trade is also international: thousands of Iranian women and girls have been sold into sexual slavery abroad.

The head of Iran’s Interpol bureau believes that the sex slave trade is one of the most profitable activities in Iran today. This criminal trade is not conducted outside the knowledge and participation of the ruling fundamentalists. Government officials themselves are involved in buying, selling, and sexually abusing women and girls.

Many of the girls come from impoverished rural areas. Drug addiction is epidemic throughout Iran, and some addicted parents sell their children to support their habits. High unemployment – 28 percent for youth 15-29 years of age and 43 percent for women 15-20 years of age ‑ is a serious factor in driving restless youth to accept risky offers for work. Slave traders take advantage of any opportunity in which women and children are vulnerable. For example, following the recent earthquake in Bam, orphaned girls have been kidnapped and taken to a known slave market in Tehran where Iranian and foreign traders meet.

Popular destinations for victims of the slave trade are the Arab countries in the Persian Gulf. According to the head of the Tehran province judiciary, traffickers target girls between 13 and 17, although there are reports of some girls as young as 8 and 10, to send to Arab countries. One ring was discovered after an 18 year-old girl escaped from a basement where a group of girls were held before being sent to Qatar, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. The number of Iranian women and girls who are deported from Persian Gulf countries indicates the magnitude of the trade. Upon their return to Iran, the Islamic fundamentalists blame the victims, and often physically punish and imprison them. The women are examined to determine if they have engaged in “immoral activity.” Based on the findings, officials can ban them from leaving the country again.

Police have uncovered a number of prostitution and slavery rings operating from Tehran that have sold girls to France, Britain, Turkey, as well. One network based in Turkey bought smuggled Iranian women and girls, gave them fake passports, and transported them to European and Persian Gulf countries. In one case, a 16-year-old girl was smuggled to Turkey, and then sold to a 58-year-old European national for $20,000.

In the northeastern Iranian province of Khorasan, local police report that girls are being sold to Pakistani men as sex-slaves. The Pakistani men marry the girls, ranging in age from 12 to 20, and then sell them to brothels called “Kharabat” in Pakistan. One network was caught contacting poor families around Mashad and offering to marry girls. The girls were then taken through Afghanistan to Pakistan where they were sold to brothels.

In the southeastern border province of Sistan Baluchestan, thousands of Iranian girls reportedly have been sold to Afghani men. Their final destinations are unknown.

One factor contributing to the increase in prostitution and the sex slave trade is the number of teen girls who are running away from home. The girls are rebelling against fundamentalist imposed restrictions on their freedom, domestic abuse, and parental drug addictions. Unfortunately, in their flight to freedom, the girls find more abuse and exploitation. Ninety percent of girls who run away from home will end up in prostitution. As a result of runaways, in Tehran alone there are an estimated 25,000 street children, most of them girls. Pimps prey upon street children, runaways, and vulnerable high school girls in city parks. In one case, a woman was discovered selling Iranian girls to men in Persian Gulf countries; for four years, she had hunted down runaway girls and sold them. She even sold her own daughter for US$11,000.

Given the totalitarian rule in Iran, most organized activities are known to the authorities. The exposure of sex slave networks in Iran has shown that many mullahs and officials are involved in the sexual exploitation and trade of women and girls. Women report that in order to have a judge approve a divorce they have to have sex with him. Women who are arrested for prostitution say they must have sex with the arresting officer. There are reports of police locating young women for sex for the wealthy and powerful mullahs.

In cities, shelters have been set-up to provide assistance for runaways. Officials who run these shelters are often corrupt; they run prostitution rings using the girls from the shelter. For example in Karaj, the former head of a Revolutionary Tribunal and seven other senior officials were arrested in connection with a prostitution ring that used 12 to 18 year old girls from a shelter called the Center of Islamic Orientation.

Other instances of corruption abound. There was a judge in Karaj who was involved in a network that identified young girls to be sold abroad. And in Qom, the center for religious training in Iran, when a prostitution ring was broken up, some of the people arrested were from government agencies, including the Department of Justice.

The ruling fundamentalists have differing opinions on their official position on the sex trade: deny and hide it or recognize and accommodate it. In 2002, a BBC journalist was deported for taking photographs of prostitutes. Officials told her: “We are deporting you … because you have taken pictures of prostitutes. This is not a true reflection of life in our Islamic Republic. We don’t have prostitutes.” Yet, earlier the same year, officials of the Social Department of the Interior Ministry suggested legalizing prostitution as a way to manage it and control the spread of HIV. They proposed setting-up brothels, called “morality houses,” and using the traditional religious custom of temporary marriage, in which a couple can marry for a short period of time, even an hour, to facilitate prostitution. Islamic fundamentalists’ ideology and practices are adaptable when it comes to controlling and using women.

Some may think a thriving sex trade in a theocracy with clerics acting as pimps is a contradiction in a country founded and ruled by Islamic fundamentalists. In fact, this is not a contradiction. First, exploitation and repression of women are closely associated. Both exist where women, individually or collectively, are denied freedom and rights. Second, the Islamic fundamentalists in Iran are not simply conservative Muslims. Islamic fundamentalism is a political movement with a political ideology that considers women inherently inferior in intellectual and moral capacity. Fundamentalists hate women’s minds and bodies. Selling women and girls for prostitution is just the dehumanizing complement to forcing women and girls to cover their bodies and hair with the veil.

In a religious dictatorship like Iran, one cannot appeal to the rule of law for justice for women and girls. Women and girls have no guarantees of freedom and rights, and no expectation of respect or dignity from the Islamic fundamentalists. Only the end of the Iranian regime will free women and girls from all the forms of slavery they suffer.

The author wishes to acknowledge the Iranian human rights and pro-democracy activists who contributed information for this article. If any readers have information on prostitution and the sex slave trade in Iran,

-

14:55

14:55

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

1 year agoGood and The Bad Life in IRAN Before and After The Economic Islamic Revolution !

685 -

27:03

27:03

Geodiode - Exploring Our World Through Video

3 years ago $0.07 earnedIran: History, Geography, Economy & Culture

207 -

15:28

15:28

RydroMusic

8 months agoPahlavi's Iran: A False Utopia | Iran Before the Islamic Revolution

102 -

8:46

8:46

YMCMB Academy

1 year agoThe History of Saudi Arabia

1.94K -

18:09

18:09

vietrandy

7 months agoSaudi Arabia - Iran in agreement - The end of this age Look Up Saints

442 -

32:46

32:46

DiggTrueInfor17

1 year agoIRAN-SAUDI ARABIA Peace Agreement Could change Middle east future?

6241 -

45:28

45:28

Mikhaila Peterson

1 year agoMass Protests, Morality Police, and Iranian Bravery | King Raam 162

2.98K32 -

0:27

0:27

AmbientSanctuary

6 months agoShah Mosque: A 30-Second Visual Feast! #Shorts #Trivia #Facts #Travel #Tourism #Iran #History #Art

7 -

0:52

0:52

Rik's Mind Podcast

1 year agoKamin Mohammadi on The Rich History and Culture of Iran | Riks Mind 105

156 -

1:27:18

1:27:18

kushalmehra1981

1 year agoIslamism In Iran

7