Thousand's Dead In U.S.A. Now & Shot In Head By Police & Civil Asset Forfeiture Abuse

New Proof That Police Use Civil Forfeiture To Take From Those Who Can’t Fight Back Nassir Geiger spoke with the wrong person at the wrong time and it cost him hundreds of dollars and his car. Nassir was a victim of Philadelphia’s predatory civil forfeiture scheme that operated from a shady “courtroom” at City Hall. For years, police and prosecutors seized cash, cars and even homes and then took the property for themselves. Worse still, new data show that the police preyed on people in minority and low-income areas—in other words, people who could least afford to fight back.

Undercover Police abuse of civil asset forfeiture laws has shaken our nation’s conscience. Civil forfeiture allows police to seize — and then keep or sell — any property they allege is involved in a crime. Owners need not ever be arrested or convicted of a crime for their cash, cars, or even real estate to be taken away permanently by the government.

Also A officer told new world order and said if its late at night and very dark area. i pull over a van or car over. yes one time with about $40.000 in cash and some drugs too. i will ask man or woman to step out of car etc. i shot them 2 times each in head and take the money and leave area. i can make up to a millions dollars a years with money and drugs sales. very sad but true! I asked how it worked.... He said... I look for out of town lic. plate or rental cars mostly. this officer is missing now or gone out of the area. as of 2018 time and date.

Every day, on average, 316 people in America are shot in murders, assaults, suicides and suicide attempts, unintentional shootings, and police intervention. Every day, 106 people die from gun violence. 39 are murdered - 64 kill themselves - 1 is killed unintentionally - 1 dies but the intent is unknown - 115,551 people in America are shot in murders, assaults, suicides & suicide attempts, unintentional shootings, or by police intervention.

In the United States, law enforcement agencies have the power to seize the assets of those suspected of criminal activity. On its face, this seems somewhat reasonable. However, the threshold for suspicion of criminal involvement is perilously low and allows law enforcement agencies to abuse the power afforded through civil forfeiture. Many innocent citizens have had their property seized as a result, and the following instances of civil forfeiture abuse are particularly egregious.

Nassir’s troubles began when he stopped to say hello to a friend at a McDonald’s in northeast Philadelphia. What Nassir didn’t know was that the friend had just been arrested for drug possession. A few minutes after ending the conversation and driving away, Nassir was pulled over. His car was searched and although no drugs or even drug residue were found, the officers seized the car and $580 cash because they found empty ziplock bags. The police gave Nassir a receipt for only $465 rather than the full amount taken and no receipt for his car. Nassir’s court-appointed attorney recommended that he take a plea deal that would result in a clear record if he paid a $200 fine and completed 20 hours of community service. This plea deal didn’t include the government taking his car or cash, so Nassir thought he would get both back. He was wrong.

Instead, prosecutors filed a separate civil forfeiture action to take his property. They almost certainly would not have been able to claim his car or his cash through a criminal trial since the supposed offense carried such a light punishment. But in civil forfeiture, the property, and not the person, is on trial. Civil forfeiture is a process already prone to abuse, but in Philadelphia property owners were at an even greater disadvantage than typical. Property owners were summoned to Courtroom 478 at City Hall, but there was no judge in the room. The show was run by prosecutors, the same people who filed the forfeiture actions and who stood to benefit financially from successful forfeitures.

When Nassir appeared in Courtroom 478, he was told to fill out paperwork, which he had to complete without the benefit of a court-appointed attorney. He was told to come back in another six weeks for another hearing. At that second hearing, prosecutors told Nassir he could get his car back only if he paid the $1,800 in storage fees that had been piling up.

Without his car, Nassir’s 10-minute car commute turned into a 45-minute ordeal requiring two buses. He eventually bought another car, which required a new loan and cost him more to insure because it was financed.

Philadelphia started to reform its abusive forfeiture system only after Nassir and other city residents filed a class action lawsuit with the Institute for Justice. The bad press from the suit (which included a segment on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver) persuaded the city to negotiate a settlement. The settlement included both mandated reforms and a fund to compensate its victims.

Because Philadelphia abused many people over many years, more than 30,000 people were eligible for compensation. This made it possible for the Institute for Justice to survey victims and release a report, “Frustrating, Corrupt, Unfair: Civil Forfeiture in the Words of Its Victims,” released just this week.

The major findings confirm what has long been speculated about civil forfeiture’s victims. First, it is a process that disproportionately targets disadvantaged communities. Two-thirds of survey respondents were Black, 63% earned less than $50,000 annually and 18% were unemployed. And forfeitures clustered in predominantly minority and low-income areas, like where police seized Nassir’s car and cash.

Similar to how Philadelphia went after Nassir for empty baggies, law enforcement typically wasn’t using civil forfeiture to fight serious crime. Only 1 in 4 survey respondents was ever convicted of a crime. And like Nassir, many of those who were convicted pleaded to low-level offenses that were eventually scrubbed from their record. Moreover, half of all reported seizures were worth less than $600. One respondent even said police seized his crutches.

The report also found that fighting civil forfeiture, difficult for anyone, was even harder for the working poor. In Philadelphia, missing a single court date often meant losing your property forever. Yet prosecutors would frequently reschedule court dates with little or no notice, forcing people to go to court a half-dozen times or more to resolve their case. This chicanery put people with less flexible work schedules at a great disadvantage. Additionally, survey respondents with less education were less likely to get their property back.

This report, for the first time, paints a picture of who suffers when the scales of justice are tipped in the direction of the government. The stories in the report reinforce why civil forfeiture needs to be eliminated. If the government is going to take someone’s property, it should charge them with a crime and take that property as part of a criminal trial in which it has proven the person guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Anything less violates the principles upon which the United States was built.

A Chinese woman who had a bullet lodged in her head for 48 years without knowing about it has had it removed by doctors.

The 62-year-old woman, identified in local media only by her surname, Zhao, had a bullet 2.5cm long and 0.5cm in diameter extracted from her head. She had gone to the doctors complaining about a chronic stuffy nose, headaches and swollen lymph nodes that had bothered her for 10 years, Want China Times reported.

“I am happy that the bullet did not kill me, I am grateful to it for allowing me to live and have the opportunity of my life with my family,” said Zhao, from Liaoning province. The question of how she went 48 years without knowing about the bullet resulted in conflicting media reports.

According to Want China Times, Zhao said she was hit on her right temple when she was 14 years old. At the time, she thought it was a stone. But the Shanghaiist reported the woman as saying she had been hit by a stray bullet as a girl, but only felt minor pain and decided she would live with it.

The ACLU works in courts, legislatures, and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties that the Constitution and the laws of the United States guarantee everyone in this country. Police abuse of civil asset forfeiture laws has shaken our nation’s conscience. Civil forfeiture allows police to seize — and then keep or sell — any property they allege is involved in a crime. Owners need not ever be arrested or convicted of a crime for their cash, cars, or even real estate to be taken away permanently by the government.

Forfeiture was originally presented as a way to cripple large-scale criminal enterprises by diverting their resources. But today, aided by deeply flawed federal and state laws, many police departments use forfeiture to benefit their bottom lines, making seizures motivated by profit rather than crime-fighting. For people whose property has been seized through civil asset forfeiture, legally regaining such property is notoriously difficult and expensive, with costs sometimes exceeding the value of the property. With the total value of property seized increasing every year, calls for reform are growing louder, and CLRP is at the forefront of organizations seeking to rein in the practice.

Civil asset forfeiture: I'm a grandmother, not a drug lord. Why can police take my property? It shouldn't take six years and the threat of legal action to be treated fairly. I hadn't been accused of any crime. I shouldn't have been punished. Six years ago, police showed up at my home at night in Massachusetts, demanded the keys to my car and threatened damage to it if I didn’t comply. They confiscated my car, but I’m not a criminal. In fact, I wasn’t even accused of a crime. So why have I been treated like one? Don’t I have any rights?

Turns out I’m not alone. I’m one of countless Americans who have had their property taken away under civil asset forfeiture laws, which allow police to take property if they suspect it was used in a crime. It adds up. There are so many of us that billions of dollars of property are seized every year. Unlike so many other victims, I decided to fight the government to get my property back.

My story began in March 2015 when I let my son, Trevice, borrow my car. Police in Berkshire County suspected that he was selling drugs, so they seized my car under the state’s civil asset forfeiture law, even though I had not been accused of any crime. But I had no idea that my son might have been involved in illegal activities when he was charged with a crime.

Turns out, some people are above the law:Police act like laws don't apply to them because of 'qualified immunity.' They're right.

At least 35 states have these kinds of laws on the books, allowing police to take, keep and profit from someone’s property without even charging them with a crime, much less convicting them of one. While civil forfeiture was originally designed to punish criminals like pirates and drug lords, it’s average Americans like me who are now frequently targeted.

Police theft finances more police theft

I was shocked when I learned what the government does with the property that is forfeited. Simply put, these laws are funding the police. Law enforcement agencies can keep the property, sell it and use 100% of the proceeds to pad their budgets. And there is no requirement that the value of the items seized be proportional to the crime allegedly committed. The amount of money captured is staggering. Since 2000, states and the federal government have collected at least $68.8 billion, according to an Institute for Justice report.

Not surprisingly, the deck is stacked against innocent people like me. In many cases, it costs more to hire an attorney to fight the government than the forfeited property is worth. The Institute for Justice reports that “conservatively, hiring an attorney to fight a relatively simple state forfeiture case costs at least $3,000 — more than double the national median currency forfeiture.”

Many Americans simply cannot afford a lawyer and can’t wade their way through the legal system and overcome the laws that make it too easy for the government to wrongfully take their property. It can truly be an overwhelming and frightening experience. That’s how I felt about my predicament. There are really no words for the stress caused by this forfeiture. But I knew I needed to fight back. Thankfully, with pro bono representation from the Goldwater Institute, I did just that.

The government might have kept my property for good, but fortunately, shortly after I got legal help, Berkshire County told me last week that they would return my car to me. However, it shouldn’t have to take six years and the threat of legal action to be treated fairly. I was so fortunate to get that help — but what about all the other innocent Americans who can’t afford it? Getting my car back has a particularly personal significance: In December 2018, my son Trevice was tragically killed in an incident unrelated to the forfeiture. My car is one of the biggest items of value I had to my name, and so I had been hoping to pass it along to Trevice’s daughters.

I am no drug kingpin, no crime lord. I’m an average American, fighting against a system profiting off Americans who haven’t run afoul of any law. States ought to turn their attention to doing away with this form of government theft, instead of turning a blind eye to the abuse of innocent people.

Father And Son Subjected To ‘Profiling For Profit’ Stephen Skinner and Jonathon Brashear were passing through New Mexico on a road trip to Las Vegas, when they were pulled over for traveling 8 kilometers (5 mi) over the speed limit. The New Mexico state trooper who made the initial stop issued a written warning for the speed infraction and then asked for permission to search the vehicle, which was a rental car.A drug dog was called in, and the trooper dismantled parts of the vehicle during the course of the search but did not find any evidence of drugs. The trooper did note, however, the presence of nearly $17,000 in cash. The trooper detained Skinner and Brashear for two hours, referring to Skinner pejoratively by calling the 60-year-old African-American man “boy,” before telling him upon his release that “it wasn’t over yet.”Once the pair reached Albuquerque, they were pulled over again—this time for an improper lane change by the Albuquerque Police Department. This stop, however, was supported by the presence of an officer with the Department of Homeland Security, who promptly seized the cash and the car, dropping off Skinner and Brashear at the airport with no money and no means of transportation.It took two years and the intervention of the ACLU before the money was returned to Skinner and Brashear, and the incident was not the first time that Albuquerque officials faced criticism for abusing forfeiture laws: Bernalillo County and Darren White, the former sheriff, were required by a judge to pay in excess of $3 million in damages to people who had cash seized by sheriff’s deputies, as it had been determined that this money was seized with the primary intent of supplying additional funds for the police budget.

Restaurateur Has One-Year-Old Baby Taken Away And $50,291 Seized In another incident involving the same Tenaha police officer and district attorney, restaurant owner Dale Agostini was pulled over on the same stretch of highway as Jennifer Boatright and Ron Henderson for the same reason: driving in the left lane without passing. After using what turned out to be an untrained police dog to sniff the vehicle, officers found over $50,000 in cash but no evidence of drugs. Agostini explained to the officers that he had family in the area and he intended to buy restaurant equipment at a local auction with the cash he was carrying. At the time, Agostini was traveling with his fiance and their one-year-old child, along with a cook who worked at Agostini’s restaurant.Agostini and the passengers were informed by Lynda K. Russell, the district attorney who had arrived on the scene, that they would face charges for money laundering and for engaging in organized criminal activity, and the baby would be turned over to Child Protective Services. The car, the $50,000, six cell phones, and an iPod were all seized.When Agostini learned that he was being jailed and his child was being taken away, he asked if he could kiss his son goodbye, a request that was summarily denied. Russell was later heard on tape coldly joking about Agostini’s request, recalling that she said, “No, kiss me.” Agostini also asked to be permitted to speak with a lawyer, only to be told such a request could not be granted until he had spent at least four hours in jail. No criminal charges were ever filed.

Couple Forced To Choose Between $6,037 And Custody Of Their Children When Ron Henderson was pulled over by police in Tenaha while traveling from Houston to Linden, Texas, the officer informed him that he had been pulled over for traveling in the left lane for over half a mile without passing. During the stop, the officer claimed to smell marijuana. When asked if there were any drugs in the car, Henderson and his girlfriend, Jennifer Boatright, replied that there were not. The couple then consented to a search of the car, which yielded a glass pipe and $6,037 in cash, which the couple said they intended to use to buy a car when they arrived in Linden. No drugs of any kind were found in the vehicle.The officers escorted Boatright and Henderson to the local police station, where they met with the county’s district attorney, Lynda K. Russell. The DA informed the couple that they had two options: They could be charged with money laundering and child endangerment, or they could simply sign a waiver to turn the $6,037 over to the city. The DA informed the couple that being charged with multiple felonies would land Henderson and Boatright in jail, and Child Protective Services would take custody of their children as a result, so the couple signed the cash over to the city rather than lose their children and face felony charges.The situation experienced by Boatright and Henderson is a common one in Tenaha, as officers take full advantage of civil forfeiture laws as a means of generating revenue. After the city marshal fielded constant complaints from drivers passing through Tenaha who had endured similar circumstances, he simply complimented the officer on a job well done, saying, “Be safe, and keep up the good work.”

Donald Scott Killed During Drug Raid Aimed At Seizing 250-Acre Malibu Property In October 1992, multiple law enforcement agencies executed a search warrant on the home of Donald Scott, a somewhat reclusive millionaire who had rejected repeated overtures made by federal officials to sell his property. The property, which had archaeological ties to the Chumash, was believed by federal officials to be the site of a large marijuana growing operation. During the raid on the home, Scott’s wife screamed, “Don’t shoot me! Don’t kill me!” after deputies entered the home, which led Scott, who had been sleeping, to check on the disturbance while carrying a revolver.When deputies encountered Scott, they demanded that he lower his gun. As he lowered the handgun, deputies opened fire and killed him on the spot. The deputies and other law enforcement officials then began their search of the home, leaving Scott on the floor unattended. In a recorded phone call from a neighbor that took place shortly after the shooting, the sheriff’s deputy who answered the phone told the neighbor that Scott, whose body was still lying in a pool of his own blood, was “busy.”During the subsequent search of the property, officials turned up no evidence of any marijuana on the property. While the search for marijuana was used as the rationale for the raid on Scott’s home, it was later discovered that officials from multiple law enforcement agencies had discussed seizing the home and had even researched appraisals of similar properties in the area before executing the raid. In a report written by Michael Bradbury, the District Attorney of Ventura County, it was determined that property forfeiture was indeed one of the primary motivations for the raid.

Philadelphia Family Has Home Seized Due To Son’s Drug Use After their son Yianni was arrested for possession of $40 worth of heroin, Christos and Markella Sourovelis had their home seized by officials in Philadelphia, who contended that not only was Yianni in possession of heroin but that he was also selling it. The sales allegedly took place in the home or in front of the home, and though the Sourovelis family had no knowledge of the criminal activity, civil asset forfeiture laws allowed officials to evict the Sourovelis family from the home with no prior notice.Though the Sourovelis family was ultimately able to return to their home eight days after they were evicted, the district attorney’s office used the forfeited house as leverage to ensure that Yianni, who was 22 at the time, would be permanently banned from the home to prevent future drug sales. While the Sourovelises were back in the home relatively quickly, the process of resolving the case took several months of court proceedings to determine whether or not they would be able to permanently remain in their home.

Traveler Has $11,000 Seized From Luggage Alleged To Smell Of Marijuana Charles Clarke was waiting to board a flight to Orlando when police approached him and questioned him about the contents of his luggage. A police dog had detected the smell of marijuana in a bag checked by Clarke, and Clarke admitted that he had smoked marijuana on the way to the airport. He also asserted to police that there was no marijuana in the bag itself.Knowing that there was nothing illegal in the bag, Clarke consented to a search of its contents. When the police asked if Clarke was carrying any cash with him, he willingly informed officers that he had $11,000 and even showed them where it was. Since he could not provide any immediate documentation proving the $11,000 was lawfully earned, the police seized the money under the assumption that it was either the profits of narcotics trafficking or was being carried with the intent of purchasing narcotics.Since Clarke was unaware that police could lawfully seize what amounted to his life savings without any tangible evidence of wrongdoing, he became combative when officers informed him they would be taking his money. In trying to keep the officers from his cash, he pushed one of them away, leading police to charge him with assault of a police officer, disorderly conduct, and resisting arrest.The assault charge was immediately dismissed, but Clarke had to agree to perform community service to get the disorderly conduct and resisting arrest charges dropped. Of course, the $11,000 will remain with law enforcement unless Clarke is able to successfully contest the legality of the forfeiture.

Motel Seized From Owner Due To Drug Arrests Of Patrons In 2009, Russ Caswell was informed by federal agents that his motel was being seized because the property had been used during the commission of drug crimes. The crimes cited by the federal agents occurred over a 20-year period and included 15 arrests in total, but all of the arrests were of patrons of the motel, not of Caswell or any of his employees. So though Caswell and his staff had actually helped police in securing many of these arrests and had not been even remotely implicated in any criminal activity, the federal agents still sought to seize his property.Even though the case seemed “ludicrous” to Caswell, he was still forced to endure three years of litigation in which the government tried to permanently seize his property, which he owned outright and was worth in excess of $1 million. He paid $60,000 to fight the suit, and even then, Caswell had to rely on pro bono work from an attorney to continue to plead his case. After three years of court battles, the forfeiture case was ultimately dismissed. However, as is true of all forfeiture cases, the onus was on Caswell to prove his innocence rather than on the government to prove his guilt.

Driver Loses $3,500 For ‘Looking Like A Drug Dealer’ In a case highlighted in an NAACP letter to Congress, an African-American man was pulled over traveling from Virginia to Delaware, allegedly for having a taillight out. The taillight had actually been functioning properly, but this ploy allowed the officer to size up the driver for a potential search and seizure through the use of civil asset forfeiture. The driver, according to the officer, “looked like a drug dealer,” which was apparently reason enough for the officer to enlist a drug-sniffing dog to search the man’s car.After the search did not turn up any drugs or any other evidence of illegal activity, the officer asked if the driver was carrying any guns, drugs, or money. Though the driver had no firearms and no drugs, he did state that he had $3,500 in cash. The officer promptly seized the driver’s cash. Despite not finding any evidence that could support an arrest, they said that the money could only be the profits of drug dealing and was thus subject to legal seizure under civil forfeiture laws. The driver was never charged with any crime.

Philadelphia Couple’s Home Seized After Son Arrested For Marijuana In 2012, Leon and Mary Adams had their property seized because their son, Leon Jr., had allegedly been selling marijuana from their front porch without their knowledge. Though Leon Jr. was indeed charged with a crime, he was alleged to have sold very small quantities—a “few $20 marijuana deals”—and the couple had nothing to do with the criminal activity. Leon Jr. had not yet been convicted of the criminal activity when the police asserted that they would be seizing the property that had been the home of Leon and Mary Adams since 1966.According to the Philadelphia Police Department, Leon Jr. had sold $20 worth of marijuana to a police informant on multiple occasions. After the first sale, the informant went to the porch of the Adams home on two more occasions to again buy $20 worth of marijuana. With evidence in the form of marked bills and the ostensible testimony of the informant, Philadelphia Police used a SWAT team in riot gear to break down the door of the home and arrest Leon Jr. A month later, Leon and Mary Adams were informed that in addition to their son being in jail while awaiting trial, their home would also be seized under civil forfeiture laws.The profits from the sale of the seized home would be split between the police and the district attorney’s office after it was sold at auction. The only reason police didn’t evict Leon and Mary Adams before they could challenge the civil forfeiture claim was that the elder Leon Adams was enduring a host of health problems and was undergoing treatment for pancreatic cancer.The forfeiture case is still pending. During an early court appearance, the assistant district attorney assigned to the Adams case brought the wrong folder to court, causing a further delay in the process.

DEA Agents Seize $16,000 From Amtrak Traveler After saving up enough money to pursue a career in the music industry, Joseph Rivers, 22, bought a one-way train ticket to Los Angeles. For DEA agents, that act alone—along with the fact that he was traveling with such a large amount of cash—was enough to suspect that Rivers was involved in drug trafficking or some other “narcotic activity.”Other passengers traveling on the Amtrak train noted that Rivers, a young African-American man, was the only passenger to be singled out by the DEA. His attorney, Michael Pancer, suggested Rivers’s race may have played a role, as he was the only black passenger on his section of the train.During the search and subsequent seizure of his cash, Rivers has said that he was completely cooperative and even allowed the DEA agents to contact his mother to corroborate his story. Rivers pleaded with agents that he would be penniless upon his arrival in California with no means of survival and no way of returning home. According to Rivers, “[The DEA agents] informed me that it was my responsibility to figure out how I was going to do that.”Rivers was not charged with any crime, and there is no indication that he ever will be, but the DEA was still able to legally seize all of the $16,000 he carried. The DEA’s explanation for the seizure was particularly troubling: “We don’t have to prove that the person is guilty. It’s that the money is presumed to be guilty.”

Your Right to Remain Silent A New Answer to an Old Question - Do Not Talk ? O.K. Don't Talk to the Police Ever! Fifth Amendment "Right To Remain Silent," When a witness is summoned to testify before a grand jury or at a judicial or legislative proceeding, the lawyer for the witness frequently concludes that it may be in the client's best interest to assert the Fifth Amendment "right to remain silent," at least with respect to certain topics. The lawyer will often give the witness a card to read aloud when asserting that privilege. But precisely what words should the lawyer advise the client to read when invoking the Fifth Amendment privilege?

For more than 100 years, lawyers have shown surprisingly little imagination or ingenuity, advising their clients to state in almost exactly these words: "On the advice of counsel, I respectfully decline to answer on the grounds that it may tend to incriminate me."

This article explains why that unfortunate language is never in the best interests of the witness, and why it naturally tends to sound to most listeners as if the witness is somehow admitting that he cannot tell the truth without confessing that he is guilty of some crime. The article also points out that this archaic invocation is not required by either the language or the theory of the Fifth Amendment, nor by the most recent controlling Supreme Court precedents. The article concludes with a suggestion for an entirely new formulation for invoking the privilege, one which gives greater protection to the rights of the witness and also more faithfully captures what the Supreme Court of the United States has written about the nature of this precious constitutional privilege. Keywords: Fifth Amendment, self-incrimination, right to remain silent. Why You Should NEVER Talk to the Police. Period. “The police are at my door. They want to talk to me. They told me I am not a suspect. I did absolutely nothing wrong. I have nothing to worry about. They can’t arrest me or do any harm to me if I did nothing wrong, right?”

Wrong.

“But I committed no crime. Took nobody’s life. I didn’t even see anything criminal happen. I don’t know anyone who may have been there. I was 173 miles away when it happened. I don’t know any of the facts except from what others told me. I cannot possible be harmed, right?!”

Again, I am sorry to tell you, but you’re wrong.

What people do not realize is what they don’t know actually can hurt them. If you don’t believe me, listen to the words of former United States Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, “[A]ny lawyer worth his [or her] salt will tell the [client] in no uncertain terms to make no statement to the police under any circumstances.” Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49 (1949) (emphasis added).

Let us look at the situation a little more closely.

If the police ever ask you to come in to the station “just to chat” or are stopping by “because they only have a couple questions for you” — that means one of two things:

You are a suspect;

You are a possible suspect.

Does that clear the picture up? I sure hope so.

There is absolutely no reason for the police to want to have any discussion with you unless they know something that you (probably) don’t. May be your name was mentioned during a discussion with another potential suspect, or perhaps someone is trying to frame you, or, worse yet, you look like the person who was present on the scene and an eyewitness made a mistake in identity. This kind of thing happens all the time. And innocent people end up in custody as a result.

There is no reason to talk to the police especially if you’re innocent.

There is no reason to talk to the police; especially if you’re innocent.

Here are the top ten reasons why you should not talk to the police:*

REASON #1: Talking to the police CANNOT and WILL NOT help you.

Talking to the police cannot make any difference. Nobody can “talk their way out of” an arrest. No matter how “savvy” or intelligent you think you might be, you will not convince them that you are innocent. And any ‘good’ statements that may help you that you tell the police cannot be introduced into evidence because of hearsay rules. It’s a lose-lose situation; don’t talk to the police.

REASON #2: Even if you’re guilty, and you want to confess and get it off your chest, you still shouldn’t talk to the police.

There is plenty of time to confess and admit guilt later. Why rush the inevitable? First, hire an attorney. Let them do their work, and may be you will win your case. It is much harder to win when there is a confession. For example, do you know what happens if the cop cannot be located and there is no confession? The case gets dismissed! (It’s not a universal rule, but it’s more common than you might think.) Don’t talk to the police.

REASON #3: Even if you are innocent, it’s easy to tell some little white lie in the course of a statement.

When people assert their innocence, they sometimes exaggerate their statements and tell a little white lie on accident. That same lie could be later used to destroy your credibility at trial. Don’t talk to the police.

REASON #4: Even if you are innocent, and you only tell the truth, and you don’t tell any little white lies, it is possible to give the police some detail of information that can be used to convict you.

If you make any statement — it could later be used against. E.g. “I did not kill the guy. I was not around the area when it happened. I don’t have a gun. I never owned a gun. I never liked the guy, but, hell, who did?” Bingo. We just found your incriminating statement: “I never liked the guy.” Don’t talk to the police.

REASON #5: Even if you were innocent, and you only tell the truth, and you don’t tell any little white lies, and you don’t give the police any information that can be used against you to prove motive or opportunity, you still should not talk to the police because the possibility that the police might not recall your statement with 100% accuracy.

Nobody has a perfect memory. That includes law enforcement. Don’t talk to the police.

REASON #6: Even if you’re innocent, and you only tell the truth, and your entire statement is videotaped so that the police don’t have to rely on their memory, an innocent person can still make some innocent assumption about a fact or state some detail about the case they overheard on the way to the police station, and the police will assume that they only way the suspect could have known that fact or that detail was if he was, in fact, guilty.

If you overhear a fact from someone else and later adopt it as your own, it can be used to crucify you at trial. Don’t talk to the police.

REASON #7: Even if you’re innocent, and you only tell the truth in your statement, and you give the police no information that can be used against you, and the whole statement is videotaped, a suspect’s answers can still be used against him if the police (through no fault of their own) have any evidence that any of the suspect’s statements are false (even if they are really true).

Honest mistakes by witnesses can land you in jail. Why take the risk? Don’t talk to the police.

REASON #8: The police do not have authority to make deals or grant a suspect leniency in exchange for getting as statement.

Law enforcement personnel do not have authority to make deals, grant you immunity, or negotiate plea agreements. The only entity with that authority is the County or Commonwealth Attorney in state court and the U.S. Attorney in federal court. The officers will tell you they do, but they are lying. They have a carte blanche to lie. Don’t talk to the police.

REASON #9: Even if a suspect is guilty, and wants to confess, there may be mitigating factors which justify a lesser charge.

You may be accused of committing one offense when, in fact, you are guilty of a lesser offense. By confessing to the higher offense, you are throwing away bargaining chips. The prosecutor can try the case with your confession to the higher offense. There is no reason to confess. Don’t talk to the police.

REASON #10: Even for a completely honest and innocent person, it is difficult to tell the same story twice in exactly the same way.

If trial is the first time you tell your story, then there is no other statement by you to contradict any of your facts. However, if you have told your story twice, once at trial, and once to the police, you are probably going to mess some facts up. It’s human nature. A good cross examination by a prosecutor will tear you apart. Don’t talk to the police.

*Taken from a video lecture by Professor Dwayne. The video is reproduced in full below. https://rumble.com/v297voe-your-right-to-remain-silent-a-new-answer-to-an-old-question-do-not-talk-o.k.html

Many years ago, in the then-peaceful suburbs of where we lived on Long Island, NY, my across-the-street neighbor, an older woman, came running to our house in a panic, saying that her house had been robbed!

My father — meaning well — impulsively then ran to & and inside her house, to, I guess, see what he could see.

In the meantime, my mother called the local police, who showed up at the neighbor’s house minutes later — and promptly ARRESTED MY FATHER.

We (my mother and the neighbor, and certainly my father) tried to explain to the police that my father was innocent. But it was only HOURS LATER that the police released (and did not charge) my father.

During those few hours — as well as afterward — my mother, my sister, and I and the neighbor, were debating whether we should files charges against the police for a wrongful arrest/detainment of my father — but we ultimately decided against it, and opted for diplomacy — because, as we reasoned, (a) the police may have had what they had thought was a VALID REASON to arrest my father (although they COULD HAVE come over to OUR house to talk to the neighbor — which they did NOT do!), and (b) it would be better to maintain GOOD RELATIONS with the police than have them “hold a grudge” against us.

In hindsight, apparently “(b)” was a good decision.

-

17:24

17:24

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

7 months agoU.S.A. Government & Police States Are Seizing Money Civil Forfeiture Armored Car

6.31K6 -

4:19:14

4:19:14

The Memory Hole

4 months agoStealing Money, Drugs & Guns: NYPD Corruption Part 3 (1993)

8371 -

7:09

7:09

Info Worm

10 months ago'Fort Hood FRAUD 2009; NO DEATHS - Confirmed by Records' - 2014

428 -

2:31:46

2:31:46

The Memory Hole

4 months agoBrutality, Theft, Abuse of Authority & Active Police Criminality: NYPD Corruption Part 4 (1993)

748 -

2:34:44

2:34:44

IsabellaLive

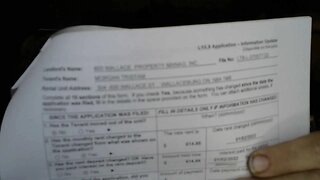

7 months agoit's Attempted Murder , rent is Auto paid, THE over $5,000 would starve any one of us dead! Crime?

25 -

11:18

11:18

Good Luck America

3 years agoMemphis Police Officer Kidnapped & Murdered Citizen - Protecting & Killing - Earning The Hate

68 -

14:14

14:14

Good Luck America

1 year agoMontgomery County Police Shoot Man In McDonald's Drive Thru - Excessive Spray & Pray Shooting

2.62K5 -

35:45

35:45

Crime Busters 101

1 year agoHow the 'Golden State Killer,' a serial rapist, murderer, evaded capture for decades

257 -

8:24

8:24

EyesOnTheState Civil Rights Government Accountability

2 years agoCop goes hands on fast 1st amendment audit arrest fail must see cop fail cop doesn't know the law

1.23K7 -

1:36

1:36

EyesOnTheState Civil Rights Government Accountability

1 year agoCop Lies Doesn't Know The Law He Is Reading! Intimidation FAIL! First Amendment Audit

1.89K4